The Spanish flu epidemic also struck Japan. Records at the time showed that more than 23.8 million people were infected with the disease in Japan, and that the total number of deaths reached about 390,000, but there are estimates that the numbers are higher than that. In any case, this is the worst infectious disease in Japanese history.

The Spanish flu epidemic spreads starting with sumo wrestlers

The Spanish flu outbreak in Japan had its origins in the news that “three sumo wrestlers, including Masago Iwa of the Oguruma training ring, died suddenly of a mysterious illness in April 1918 while on tour in Taiwan.” In the May 8 issue of the Tokyo Asahi newspaper there was an article entitled “Sumo flu is spreading these days… Sumo wrestlers line up on death beds and fall.” That article goes on to describe the situation, saying, “About a dozen sumo wrestlers roll around the tomodzuna training ring, wrapping the ‘headbands’ that sick feudal rulers in historical dramas wear on their heads.”

The official name at the time was “epidemic cold,” but it became commonly referred to as “sumo flu” or “sumo wrestlers’ disease.” The waves of the Spanish influenza epidemic in Japan can be divided into three waves. The first wave was between August 1918 and July 1919, the second wave was between September 1919 and July 1920, and the third wave was between August 1920 and July. /July 1921. In keeping with global trends, the second wave was more deadly than the first wave, with the death rate approximately 4.5 times higher. I will trace the stages of the spread of the Spanish Flu based on newspaper reports of the time.

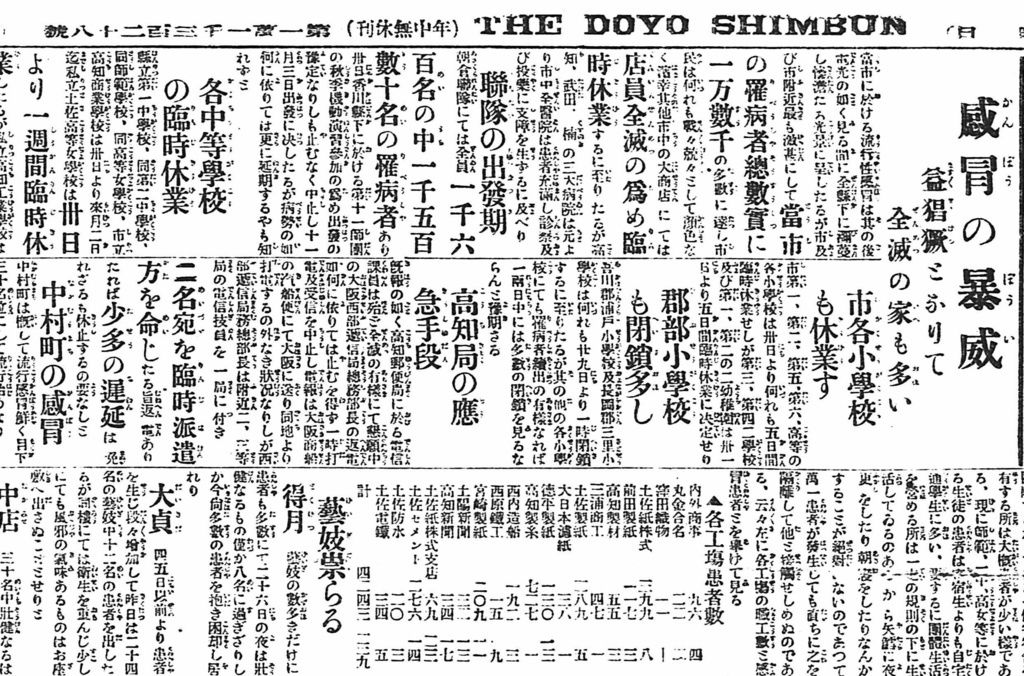

A page from a Kochi newspaper dated October 31, 1918 reporting on the first wave of Spanish influenza that occurred in different parts of the city of Kochi (© Kyodo)

The second wave in Japan was caused by the highly virulent Spanish influenza virus that entered the European war front in 1918, was spread by soldiers returning from the war, and reached Japan. The spread began in early September 1919, and by early October it had spread throughout the country, especially in the army and schools. An issue of a newspaper dated October 4 of the same year stated, “The number of epidemic cold patients in the 36th Sabai Regiment (Fukui Prefecture) has reached more than 200 people, and the regiment leadership has prevented everyone from going out and meeting people.” .

Moreover, the newspaper dated the 16th of the same month stated, “There was an outbreak of the common cold in the town of Ozo (now Ozo City) in Ehime Prefecture, where six hundred people were infected. “Many students in girls’ middle and high schools were infected with the virus, and their temperatures ranged between 39 to 40 degrees for a week.” The infections were concentrated among those between the ages of ten and thirty years. On October 24, it was reported that infections were spreading. “The recent colds that hit Tokyo have become more widespread, with dozens of students missing school at every school,” they say.

The issue issued on the 25th on the outbreak of the epidemic in schools stated, “In some areas where the Spanish cold is widespread, some schools have canceled lessons. Epidemic prevention officials were dispatched to the affected areas. “Fifty students at the First High School (currently the Faculty of Arts and Science at the University of Tokyo and the Faculty of Medicine and Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences at Chiba University) have been infected with the virus.” Thus, the epidemic spread throughout the country in October, and the number of infections and deaths reached its peak in November. Meanwhile, infections began to be reported around the world.

One of the newspapers in the issue issued on February 3, 1920, conveys the severity of the second wave’s lethality under the headline “The refusal of everyone to enter hospitals, and the collapse of all doctors and nurses.” This newspaper says, “The terrible global cold epidemic, from which there is nowhere in the world to hide, seemed to be dying for a while, but recently it has returned again and its arms have spread again, and it is spreading more and more widely.” “The number of infections is increasing, doctors are getting infected as well, and nurses are falling ill.”

Tokyo was in a state of panic, and many citizens fled from it. “Everywhere in Atami City is crowded with people who have fled cold spots, and even the futon rooms (traditional Japanese bedding) are overcrowded,” the February 19 issue of a newspaper reported. Moreover, a newspaper in its June 14 issue describes the tragic situation at that time, saying, “When the deadly cold epidemic intensified, the coffins were piled up, some with different names and bodies.”

The second wave seemed to subside in July 1920, but a third wave of the epidemic began in August. On January 11, 1921, a newspaper reported, “It seems that the terrifying epidemic cold has spread again throughout the country and is at its peak, and we are in an era of fear due to continuing deaths.” If someone coughs, even just one cough, he should not leave his house. Because of this person, many people may become infected.” Around this time, mask shortages became a social issue, and an article was published titled “Mask Prices Rise Due to Cold Epidemic.” Reports have been published indicating that the price of one mask has risen from twenty sen (each yen equals 100 sen) to 80 sen. These reports explain the situation by saying, “This is the work of fraudsters (unscrupulous merchants) and the authorities must punish them severely.”

One newspaper says in its January 11 issue, “Factories are closing their doors one after another due to the worsening outbreak of the epidemic.” “Public hot water baths, theatres, cinemas, and hair salons have witnessed a sharp decline in the number of visitors due to the outbreak of the epidemic,” she adds in its January 16 issue. A newspaper in its 22nd issue published a report on the crematorium in Sunamura (now Koto Ward) in Tokyo, stating, “223 coffins were brought in, the highest number since the opening of the crematorium, and work continued until after closing time at nine o’clock in the evening.” On the 23rd day, the newspaper reported that society was entering a state of paralysis, saying, “The means of transportation and communications have been severely damaged, and there are many people absent from work on road trains and telephone offices.”

These articles focused mainly on large cities, but the situation was dire even on remote islands. In its June 6, 1921 issue, the Hokai Times described an outbreak that occurred around the village of Robitsu on the east coast of Etorofu Island (now the Four Northern Islands), which was Japanese territory at the time, saying, “The bodies of the dead were transported To the fields, pile them on top of each other and set fire to them.” Even in Hokkaido, which had a population of 2.36 million at the time, more than 10,000 people died. The newspaper adds, “More than 100 villagers died, and it seemed that everyone was dying one by one. The village of Robitso, where the village doctors lived, was exposed to a similar situation. One of the husbands died, and an hour later his wife died.” The children were in critical condition and their conditions were miserable, and the village doctors were infected and lost their freedom of movement (…).” As the infection spread, voices calling on the government to take emergency measures increased, but the only measures that could be taken were urging people to be careful, wear masks, or refrain from leaving homes.

The fierce second wave

The following figures are extracted from the “Records of Epidemic Cold Pandemic (Spanish Flu)” compiled by the Health Bureau of the Department of the Interior (former structure of the Department of Health, Labor and Welfare) in 1922, which is considered the official government record.

Status of damage caused by the Spanish Flu in Japan

First wave (August 1918 – July 1919)

- Number of infected people: about 21.17 million people

- Number of deaths: about 260 thousand people

The second wave (September 1919-July 1920)

- Number of infected people: about 2.41 million people

- Number of deaths: about 130 thousand people

Third wave (August 1920-July 1921)

- Number of infected people: about 220 thousand people

- Number of deaths: about 4 thousand people

the total (August 1918-July 1921)

- Number of infected people: about 23.8 million people

- Number of deaths: about 390 thousand people

Source: “Records of the Epidemic Cold Pandemic (Spanish Flu)” of the Department of the Interior’s Office of Health (1922 compilation)

Death rates during the second wave of the epidemic were much higher than during the first wave. This is because the virus has become more deadly, similar to the outbreak in Europe and America. According to the clarifications attached to the records of the Health Office of the Ministry of the Interior mentioned above, “the number of infected people in the second wave was less than a tenth of the number of infected people in the first wave, but the death rate was very high, reaching more than 10% in the period from March to “In April, it was about 4.5 times the number in the first wave.” In total, the number of infected people in the country exceeded 23.8 million people, and the total deaths reached about 390,000 people. Given what the records indicate, this is the worst epidemic in Japan’s epidemiological history.

However, this number lacks data for some prefectures, as historical demographer Hayami Akira (1919-2029) indicates in his book “The Spanish Flu that Swept Japan: The First World War between Humans and Viruses” that the number of deaths may reach 450 thousand people, calculated on the basis of “Excess mortality” is when the death rate is higher than normal during an influenza epidemic.

There are various other estimates ranging from 400 to 480 thousand deaths. The age distribution of deaths is similar to what it is in Europe and the United States, where the proportion of deaths in the age group under the age of five was high, and the peak was among young men aged 30 to 34 years, and girls aged 25 to 29 years. This is very different from seasonal influenza.

At that time, every house had an infected person. In Akutagawa Ryūnosuke’s novella Tenkebu (List of the Dead), there is a scene in which a man having dinner with a geisha becomes concerned about his father, who is in critical condition due to influenza, and rushes to the hospital. It is curious that if we search in the newspapers of that time, we will find almost no criticism of the measures taken by the government against the Spanish Flu. This may be due to a lack of awareness that public health is the responsibility of the government.

The only person who spoke strong words was the poet Yosano Akiko. Akiko wrote a critical paper entitled “From the Bed of Colds,” criticizing the government and asking, “(…) Why did the government not order a temporary closure of places where many people gather (to prevent the spread of the Spanish flu)?” Akiko, who was a mother of eleven children, wrote the following verses because her family members fell one by one.

In the winter, influenza, asthma, bronchitis, and pneumonia spread, and 8 members of our family are tortured.

By 1922 even that flu had disappeared as if it were a lie. In its January 6 issue, a newspaper reported the feeling of relief among people at the time, saying, “The nation received the beginning of the influenza season with great fear, but fortunately the hand of Satan has not reached us yet this year.”

(Originally in Japanese, headline image: Japanese female students wear masks to school to prevent the spread of Spanish flu, © Photo by Pittman via Getty Images)

ظهرت في الأصل على www.nippon.com